Inside an Artificial Brain

The wonders of Artificial Intelligence (AI) are beyond question. Modern AI is built upon the development of artificial neural networks that mimic the biological neural network within a human's brain. This approach gave rise to a sub-field of Machine Learning called Deep Learning that quickly became a dominant area in AI research. Continuing in the series Intuitive AI, I explain the intuition behind important building blocks of an artificial brain that are fundamental to human cognition.

Neural System

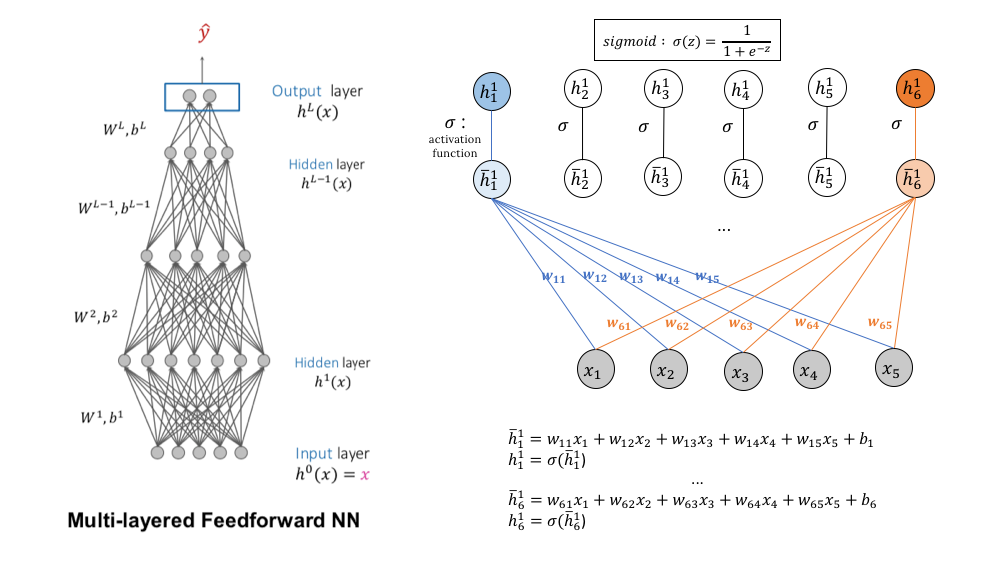

A neural network is a circuit of neurons interconnected through synapses. When a synapse is fired, it allows nervous impulses, or spikes to be transmitted between neurons, or from a neuron to a target cell. An artificial neural network is a simplified model of a human's neural network that links multiple nodes over a multi-layered structure. In this structure, a node at one layer not only receives the computational signals jointly from the nodes at the lower layer, but also contributes to computing the nodes at the upper layer. Before sending its signal, a node is passed through an activation function that basically acts as a synapse. Its relative importance in the determination of nodes upstream is quantified by a set of “synaptic” weights \(W\).

The left figure illustrates a hierarchical view of a fully connected neural network. The right one zooms in on a simple communication process between two layers:

The example uses \(sigmoid\) as the activation function. In case you question the role of activation, let’s together dive a bit in the technicality. Otherwise, feel free to skip this part.

A machine learning task is to model the relationship between an input variable \(X\) and an output variable \(Y\), both of which are generally multi-dimensional. Such relationship is represented by a function \(Y=f(X)\) that remains unknown, and the goal is to use a neural network to find a function approximating \(f\). According to the Universal Approximation Theorem, a neural network can approximate any continuous function closed and bounded by the \(n\) dimensional space given any squashing activation function and enough hidden nodes.

Each node carries a value, which is the weighted sum of all the hidden nodes below it. Without activation, the output is merely a linear combination of weights and inputs, limiting its capacity to represent complicated relationships. An activation function thus plays a crucial role in introducing non-linearities to the neural network. Because the pre-activated output can take any continuous values, another role of the activation function is to squash outputs to a certain range, harmonizing all receiving signals before sending them up through the network.

Backpropagation: Training a Neural Network

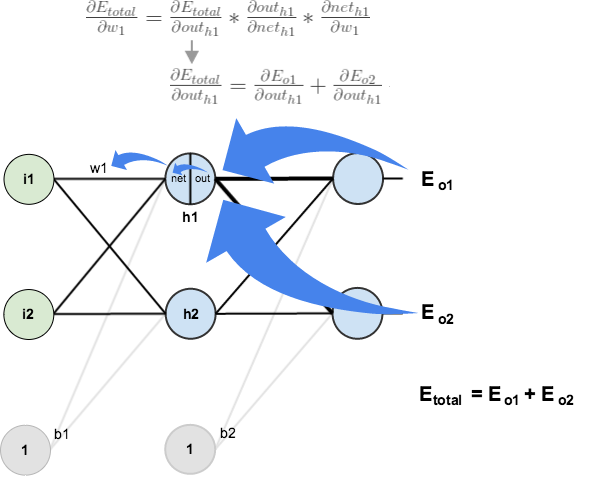

As discussed in Human Machines Are Taught, machines learn by correcting its mistakes in the form of minimizing errors, measured by how much the prediction of \(Y\) deviates from the true value. For neural nets, the synaptic weights are not static, rather iteratively updated based on the backpropagation algorithm. Because the calculations made to output the final prediction depend on \(W\), we say the network is parameterized by \(W\). The amount by which to update an individual weight value \(w_{ij}\) is proportional to how much changes in the error induced by one unit change in \(w_{ij}\) - in other words, the derivative of the error function with respect to \(w_{ij}\). The updates must be made in a way that reduces the error, and this is done by using the chain rule of calculus. The error signals thus can be viewed as feedback to the network on how to improve its performance at the next iteration.

Backpropagation forms the backbone of deep nets. The remarkable success of backprop provokes controversy among neuroscientists since a backprop-like behavior has not been directly observed in the biological brain, specifically the cortex. But because vast areas of the brain remain mysterious, it is fascinating that AI now inspires scientists to rethink human intelligence and question what we know about the brain. Although learning in the brain also takes place as a result of synaptic modifications of adjacent neurons, the retrograde dynamics as seen in artificial networks is considered problematic.

Neural responses are historically believed to be localized in the sense that a neuron only processes information from its neighbor. Thus, it is biologically implausible in terms of whether and how it further coordinates with remote neurons. Interestingly, there has been new evidence supporting the hypothesized existence of backprop-like learning structures. This is motivated by the prevalence of feedback connections in the visual cortex. These connections are particularly critical to processing visual objects that are spatially and temporally in motion. You can gain more insights about the connection between backprop and the brain from this article Artificial Neural Nets Finally Yield Clues to How Brains Learn

Attention

Attention is another breakthrough that again reinforces the strategy of cultivating artificial cognition by simulating biological neural activity. Attention underpins recent advances in sequential data processing across various applications such as machine translation or speech recognition. It has also become a critical component of machine reasoning frameworks.

Attention is driven by human’s limited capacity to process all incoming signals. We therefore rely on selectivity of attention to decide what subsets of information to be brought into awareness. Attention in the brain is both voluntary and stimulus-responsive. This means that although we are susceptible to external environments, we do have control over what to focus on and what to filter out. Attention is divided. We can simultaneously pay attention to multiple objects in parallel, and they do not necessarily involve eye movements. Visual objects that are not directly placed on the retina can be attended to, and this is related to the concepts of overt and covert attention in visual processing.

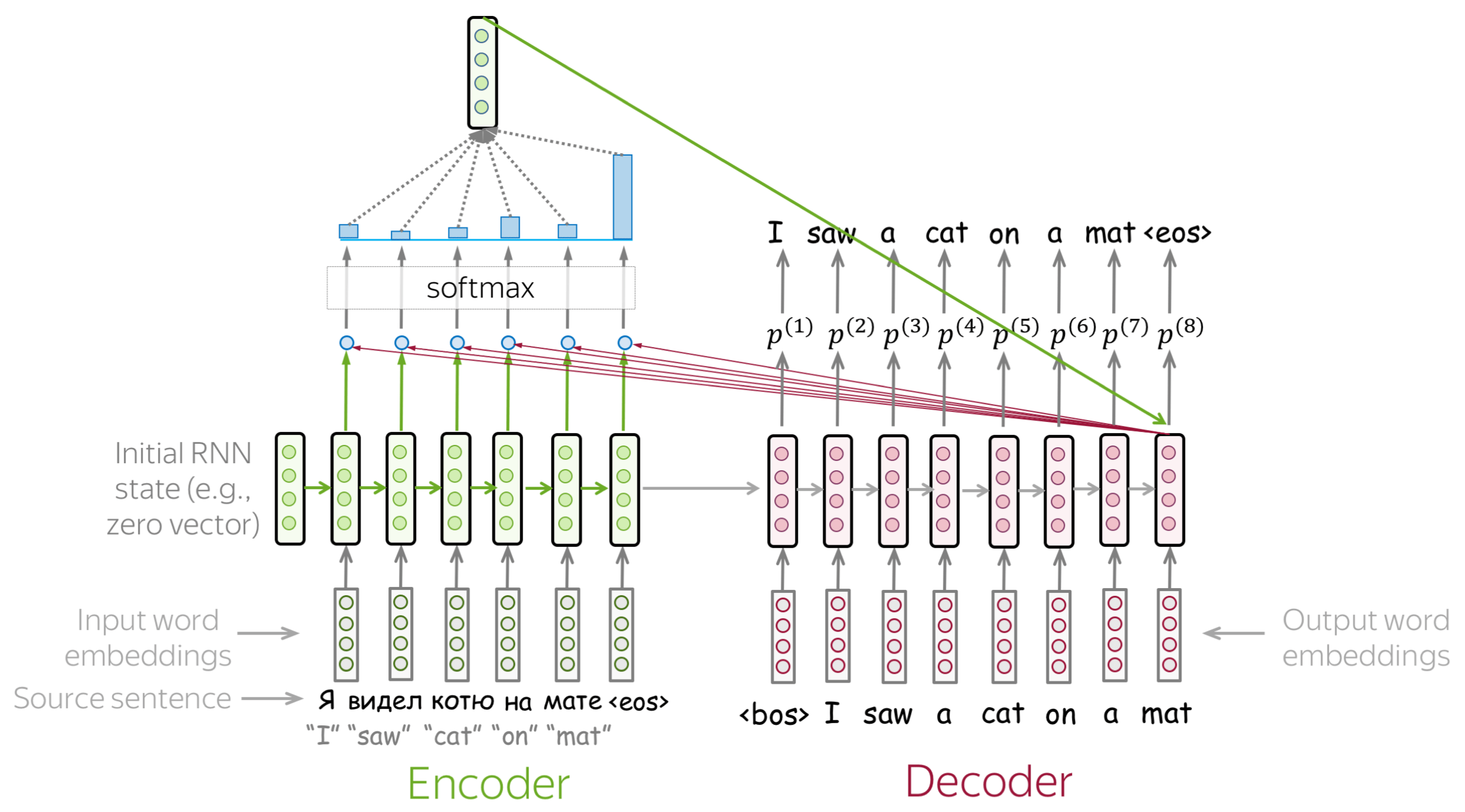

In deep learning, attention is originally proposed for natural language processing. Attention is often useful in sequence-to-sequence architecture that consists of two recurrent neural networks (RNN) tied to each other. RNN is a special architecture built specifically for sequence learning problems. One network encodes a sequence of inputs while the other is used for generating another sequence of outputs. A sequence is broken into units, and the model encodes or decodes the sequence by processing it unit by unit over a series of time steps. For example, decoding a sentence entails producing one word at a time. When the decoder predicts a word, it asks the encoder what parts of the sentence to attend to.

The attention signal must also be computerized either in the form of \(hard\) or \(soft\) attention. At every time step, \(hard\) mechanism outputs \(1\) for positions that need focusing and \(0\) for ones to be ignored. On the other hand, \(soft\) mechanism involves distributing attention to all positions such that each position is assigned a weight indicating its relative importance, typically between \(0\) and \(1\). Intuitively, hard attention informs us what to attend to and what not while soft attention says let’s focus more on some areas and less on others. Attention can be \(global\) in that all positions in the input contribute to outputting attention signals. But it can also be \(local\) wherein the attention span is restricted to a selected window, which is obviously more computationally efficient. In practice, attention weights can also be learned along with the network’s synaptic weights by being back-propagated through the error signal.

The brain is well known for its locality. Attention-related changes are associated with specific functions. For visual attention, there is a part of the brain responsible for detecting shape whereas another region captures color, semantics or some other dimension. Therefore, we expect to build within our network different attention mechanisms for different sensory inputs. The goal is purely to enhance expressivity and improve learning capacity as a result. This leads us to associative attention as a more general mechanism that allows the neural net to attend to multiple types of contents, not just positions. It often goes along with the framework of multi-head attention. Each head represents an individual function-specific attention mechanism with its own set of weights. Again, these weights are updated as the model learns and fortunately, can be computationally processed in parallelism.

Memory

Attention has been discussed so far in relation to responses to external stimuli. When the target is some internal state, we are talking about introspective attention. Being attentive to internal information stored inside the brain requires the activation of memory. Need no introduction, memory is a crucial component of human cognition, and how memory works is straightforward. Using attention, we selectively record incoming sensory inputs, encode them and shuffle them in the working/short-term memory, which only lasts under 30 seconds. Then it either decays or gets transferred into long-term memory. If the information is actively rehearsed. Memory is activated when there is a demand to retrieve information previously learned, and memory performance is measured by tasks of recall, recognition and relearning.

With that being said, attention and memory co-exist. For machine reasoning tasks, attention is incorporated in a larger memory architecture. Memory is therefore often discussed in the topic of memory-augmented neural network (MANN).

Vanilla RNNs break in the face of long sequences. The initial problem is that the operation during each time step occurs independently, thereby failing to learn the dependency naturally existing among units in a sequence. Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) is proposed to tackle this, followed by more efficient variants such as Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU). The idea is to construct long and short-term memory vectors that carry information from earlier time steps. Every node includes additional computations to determine the amount of information retained for the current processing step and amount passed onto the next. However, the model becomes increasingly forgetful when dealing with much longer sequences in later steps. This calls for explicit implementation of a memory unit.

There are plenty of methods for simulating memory inside neural nets. The proposed models mainly differ in terms of formulations and techniques, but the procedure again follows on the biological process of forming memory in the human brain. I simply summarize the intuition:

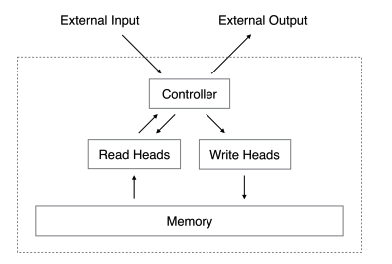

The first step is to define what to store, which can be items, relationships, modules or any program-related elements. Based on the content, memory networks can be classified into item, relational and program memory. Second, we need to structure memory storage with the fundamental design being a matrix of values. Each memory slot is assigned with an address following a certain addressing mechanism working in conjunction with writing and reading mechanisms. The former is in charge of storage and the latter is responsible for retrieval. On top of these is an algorithm that inputs a query and outputs related parts of memory. You can think of a query as a request to access the memory that conveys specificities about content, address, etc. And more concretely, the algorithm is built on some measure of association or relatedness. The entire architecture can be structured into interconnected blocks, each of which is typically a neural net to be parameterized and learned. Attention mechanism is an integral component incorporated in every stage throughout the network.

From Learning to Reasoning

In early stages of deep learning, neural networks together with backpropagation alone demonstrated remarkable ability to learn underlying complex representations and output predictions at almost the same level of accuracy achieved by humans. And as in the case of AlphaGo, AI is dominant in several tasks. But artificial intelligence is nowhere near human intelligence. Some of the popular criticisms are:

- data hungry

- prone to biases

- poorly generalize on unseen settings with similar structures

- completely ignorant of causal relations

- understand nothing about natural language beyond probability of occurences

Another caveat is the performance increases as the model scales up in both size and depth. This is highly inefficient compared to the human brain, which is said to learn so much from so little. The movement towards machine reasoning is inevitable. Attention and memory frameworks, not surprisingly, lie at the heart of today’s reasoning models.

Backpropagation has been far more effective than any traditional machine learning algorithms. Though obviously insufficient, it lays the foundation to develop better learning mechanisms. One of the beneficiaries is Reinforcement learning (RL). Reinforcement learning has invigorated interests in the AI research community due to its successful applications in robotics and potentially for self-driving car technologies. It is by nature a search problem originally, but gradient-based solutions have been shown to be more advantageous.

In a similar setup of learning through trial and error, instead of minimizing errors, the goal is to maximize rewards. The persona associated with reinforcement is an agent actively navigating in an complex game-like environment to find the optimal set of actions yielding the largest total reward. Every time the agent takes an action, it moves to a new state. At that current state, there is a policy guiding which action to take next. This is a perfect realization of Skinner’s behavioral theory of operant conditioning in an automated system.

I only introduce reinforcement learning to briefly discuss a recent inspiration from the brain. For interested readers, here is a detailed math-free explanation of reinforcement learning.

Theory of Mind

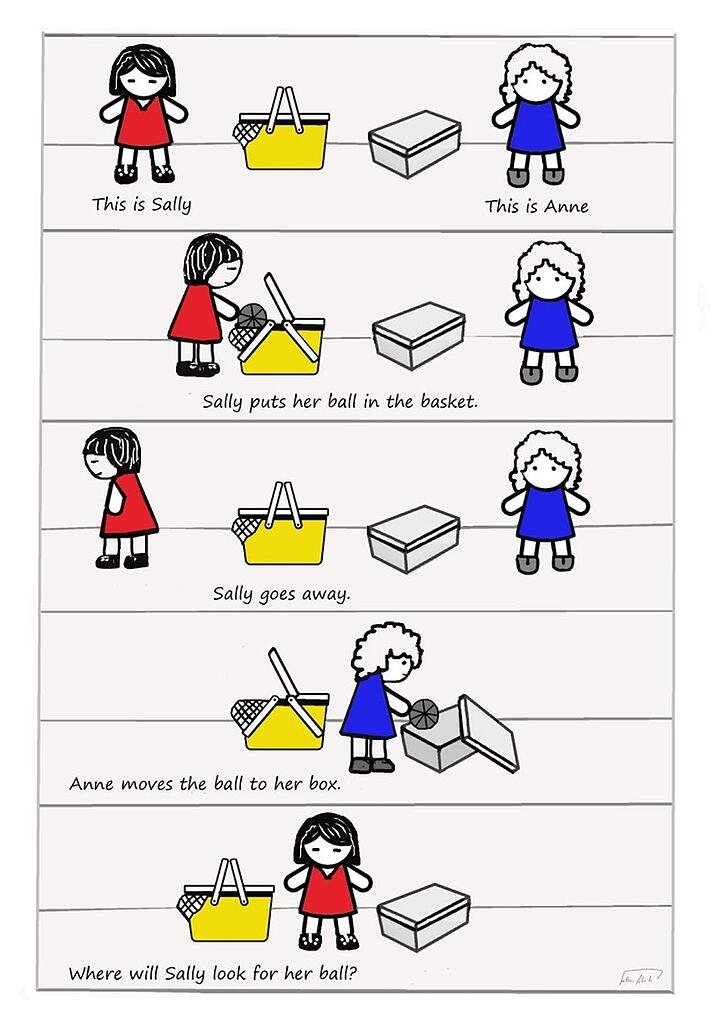

That inspiration is Theory of Mind (ToM). In psychology, ToM refers to the ability to understand or to infer other people’s minds. It is evident that intelligent machines can function independently, but to interact with other agents including humans requires them to function socially. Reasoning about others’ mental states operates at such a complex level of cognition that there is no clear path on how AI can do this effectively. Inference in real-world scenarios does not always come with a straightforward answer, and complications in human minds make task formulation for machine ToM highly challenging.

Nevertheless, there have been some attempts to model ToM using reinforcement learning frameworks. A notable approach is DeepMind's Machine Theory of Mind. They built an RL observer that learns to predict the goals, actions, states or any behavior characteristics of multiple competing RL agents. The study provides evidence that the agents do act on false beliefs (beliefs contrary to reality) but finds difficulty in formulating the means for the ToM observer to communicate whether it can infer those beliefs and how well.

Source: Internet

Outro

For the sake of reading, I avoid stuffing it up with citations. In addition to the references already included, I further list out the invaluable technical materials that contribute to my knowledge. You can always trace the citations therein for more related works.